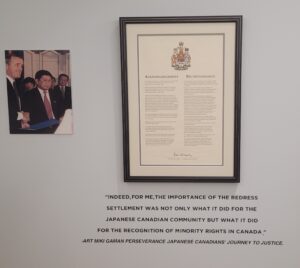

Last week, Dr. Art Miki visited the Nikka Yuko Japanese Garden to celebrate the launch of his new memoir “Gaman – Perseverance: Journey of Japanese Canadians’ Journey to Justice” and he was a guest presenter at the Golden Maple reception.

Miki is an active leader in the Japanese Canadian community having served as president of the National Association of Japanese Canadians from 1984-1992. He led the negotiations to achieve a just redress settlement for Japanese Canadians interned during the Second World War. He and his family were forcibly relocated to Manitoba sugar beet farms in 1942.

Lethbridge was also a hot bed for many of the people who were removed, especially for the local sugar beet farms in the area. “There’s quite a history of Japanese Canadians. I could relate to the experiences they had here,” says Miki. “I think it’s good to share some of our stories, especially the younger people who might not have remembered or knew about the past. I think that’s one of our obligations, is to ensure people don’t forget what happened to Japanese Canadians, so the same things don’t happen again.”

When the redress campaign first started, Miki explains, many Japanese Canadians were reluctant to support the initiative because they were afraid that by bringing the issue back up there would be racism directed at Japanese Canadians. “Especially when you’re talking about compensation. There was fear there was going to be backlash from other Canadians.”

There was even a reluctance to talk about the past, notes Miki. “From the experience of talking to Jewish people who went through the Holocaust, the same thing existed in their community, as well as other people that had gone through the trauma our community had gone through. It’s not surprising they didn’t want to share it. Especially not to let their children know because I think they were humiliated about what happened.”

“But I think the redress settlement opened that up. The fact the stories came out publicly and Canadians began to learn about it. People were more apt to share what happened to them. We’ve found there’s been quite a transition that’s taken place, where people are more open to talk about what happened to them and share it with their children. I think that’s good and part of the healing process to accept what happened and to move ahead,” he adds.

The redress settlement was a historic settlement, especially in recognition of human rights. “Prior to that, there had been no situation legally in Canada where a whole community was able to get redress from the government. In fact, we did the research and the precedent we relied on was the American Congressional Committee Report, which they indicated Japanese Americans put into concentration camps should receive $20,000. We used that as part of the precedent. The government was reluctant to go towards individual compensation because their legal people told them, ‘once you do that, you’re opening it up to a lot of other lawsuits’ and so on,” says Miki.

Just after a march on Parliament Hill in 1988, Miki says, former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney indicated to the organization the government was ready to open discussions again. “It was made clear, the issue of individual compensation would be a part of the discussion. We agreed to move ahead and that’s how the resolution came about.”

According to Miki, there were many precedents that came about in Canada as a result of the initial agreement, including Truth and Reconciliation with residential schools.